| Journal of Current Surgery, ISSN 1927-1298 print, 1927-1301 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Curr Surg and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jcs.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 2, November 2025, pages 37-41

Accuracy of the Set Tidal Volume During Intraoperative Administration of Aerosols Into the Anesthetic Circuit: An In Vitro Evaluation

Ashley Fischera, b, Amber Milemc, Joseph D. Tobiasd, e, f

aHeritage College of Osteopathic Medicine - Dublin Campus, Dublin, OH, USA

bOhio University, Athens, OH, USA

cDepartment of Respiratory Care, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

dDepartment of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

eDepartment of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA

fCorresponding Author: Joseph D. Tobias, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH 43205, USA

Manuscript submitted August 25, 2025, accepted October 30, 2025, published online November 28, 2025

Short title: Accuracy of Tidal Volume

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcs1011

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Precise control of minute ventilation is essential during the intraoperative anesthetic care of infants and children, as increased tidal volume (Vt) and consequently increased peak inflating pressure (PIP), may lead to volutrauma or barotrauma. During the intraoperative delivery of aerosolized medications such as albuterol, the additional flow required for delivery through nebulizers may alter Vt and secondarily PIP. The current study explores Vt changes during the use of a novel nebulizing device (Aerogen vibrating mesh) for the delivery of an aerosolized medication during mechanical ventilation.

Methods: Using a lung analogue model, this in vitro study compared the set Vt on the anesthesia ventilator to the internally measured inspiratory and expiratory Vt on the Avance CS2 anesthesia machine during both pressure-controlled (PC) and volume-controlled (VC) modes while administering aerosols using the Aerogen device.

Results: A total of 250 simulated breaths were delivered using the two modes of PC ventilation (PIP 15 and 20 cm H2O) and VC ventilation (Vt of 150 and 300 mL). In both PC and VC modes, there were no clinically significant differences between the set and the inspiratory or expiratory Vt or PIP at baseline when compared to those achieved following the addition of a continuous aerosol using the Aerogen device.

Conclusions: The novel technology of the Aerogen vibrating mesh device allows the delivery of continuous aerosolized medications during intraoperative mechanical ventilation using a standard anesthesia circle system. The Aerogen device can be inserted between the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit and the 15-mm adaptor of the endotracheal to easily allow the delivery of aerosolized medications without changes in mechanical ventilation parameters.

Keywords: Aerosolized medication; Mechanical ventilation; Intraoperative ventilation; Tidal volume

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Accurate control of minute ventilation, including tidal volume (Vt), is essential during the intraoperative anesthetic care of infants and children. Increased Vt, and consequently increased peak inflating pressures (PIP), may lead to volutrauma or barotrauma. Overventilation may also lead to hypocarbia with deleterious physiologic effects on end-organ oxygenation including decreased cerebral oxygenation [1-4]. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation may be provided using either a pressure-controlled ventilation (PCV) or volume-controlled ventilation (VCV) system. PCV was previously a more commonly used approach to minimize the risks of mechanical ventilation, supporting more regular Vt compared to VCV. Newer intraoperative ventilator platforms have been shown to accurately control Vt using either pressure or volume control modes [5, 6]. Even during VCV, state of the art circuitry provides accurate Vt during changes in patient resistance and compliance. However, during the care of critically ill patients, other factors may impact Vt and minute ventilation, such as the delivery of aerosolized medications.

The administration of aerosolized or inhaled medications during anesthesia, such as albuterol, may be necessary due to changes in the clinical status of the patient. In such instances, the medications are generally administered into the inspiratory limb at the connection of the endotracheal tube (ETT) to the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit to ensure effective delivery. Depending on the mode of delivery for the medication (aerosolized, meter dose-inhaler, etc.), the additional flow imposed by the aerosolizing device may impact Vt. Given these concerns during intraoperative anesthesia, it is important to compare the set Vt to the actual delivered Vt, as different aerosol devices may alter ventilation parameters during intraoperative anesthetic care. This current study evaluates the accuracy of Vt during the use of an in-line aerosolizing device to compare the fixed Vt set by the anesthesia machine (Avance CS2, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI) versus the actual Vt measured by the flow sensor during delivery of aerosolized medications.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This in vitro study was conducted at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, Ohio). As an in vitro study using a lung model analogue without human subjects, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and informed consent were not necessary. The study was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier number: NCT06232915) on January 31, 2024, and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

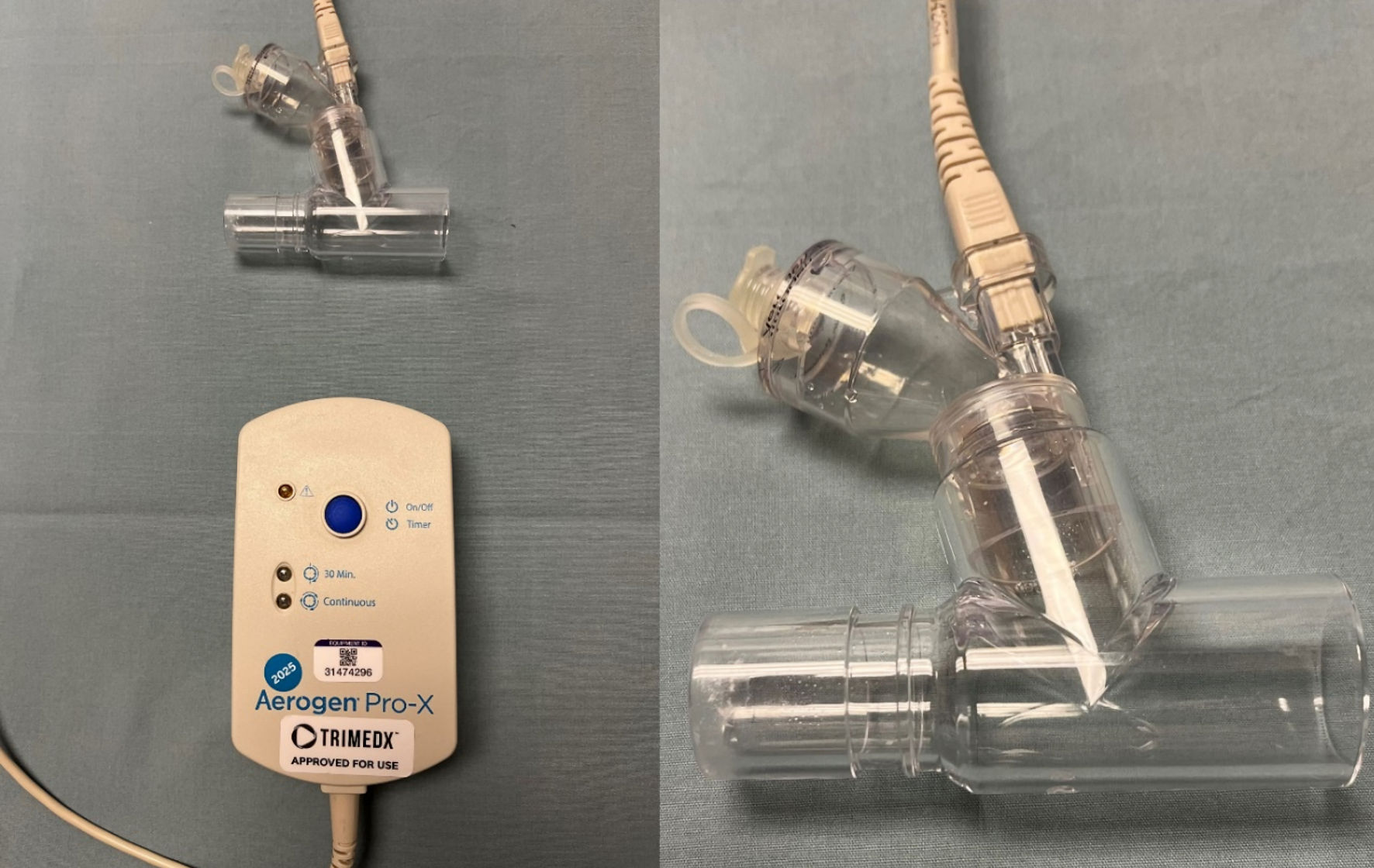

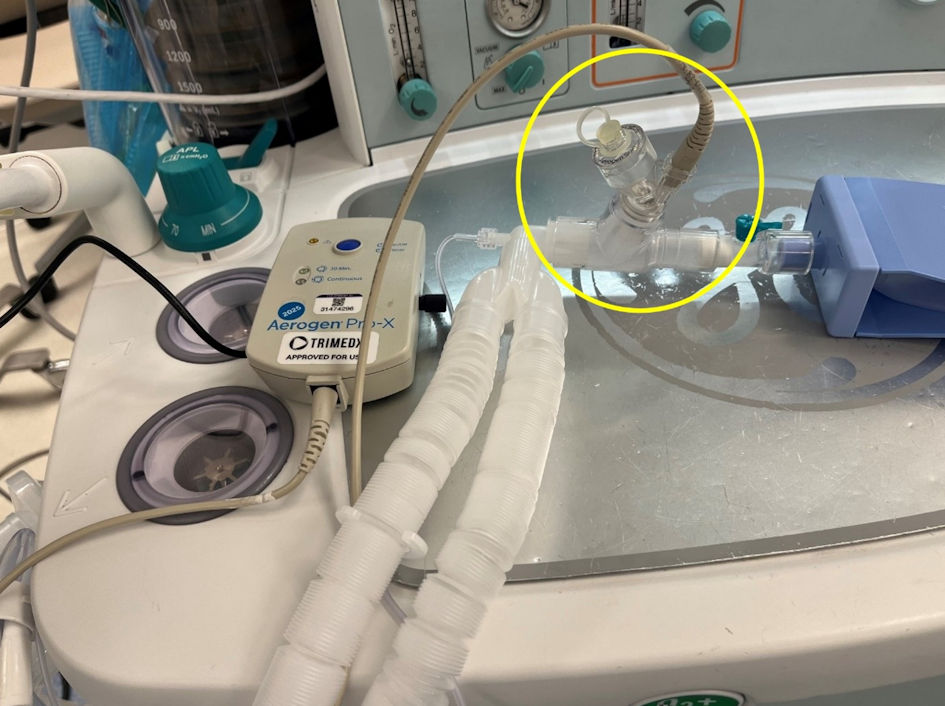

The study used an Avance CS2 anesthesia machine (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI) to deliver and analyze Vt both in the pressure and volume-controlled ventilation modes. Aerosols were delivered using an in-line Aerogen-Pro X device (Aerogen Inc, Mountain View, CA). The Aerogen device uses vibrating mesh technology (Fig. 1). In distinction to commonly used pneumatically powered nebulizing devices, the Aerogen device operates without added gas flow due to its vibrating mesh technology and can deliver an aerosol dose during mechanical ventilation that is up to nine times greater compared to standard small-volume nebulizers (Fig. 2) [7]. The Aerogen device was chosen for evaluation in this study as this is the device that is currently used at the authors’ institution. For the delivery of aerosols, the Aerogen device was placed between the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit and the 15-mm adaptor of the lung analogue model (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 1. The Aerogen device used for nebulization during the current study. The device uses vibrating mesh technology which does not require the addition of a high-flow oxygen source which distinguishes it from commonly used high-flow nebulizing devices. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Standard high flow nebulizing device that uses a high flow oxygen source to nebulize and aerosolize medications. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. For this in vitro study, the Aerogen device was placed between the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit and the 15-mm adaptor of the lung analogue model for the delivery of aerosolized medications. |

The anesthesia machine was connected to the lung analogue model using a standard expandable adult general anesthesia circuit. A full machine check was completed prior to data collection. The following ventilator parameters were kept constant throughout the study: fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) 40%, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 5 cm H2O, inspiratory time 1 s, fresh gas flow 2 L/min, and respiratory rate 15 breaths/min. Vt (inspiratory and expiratory) values were collected from the internal spirometers of the anesthesia machine. As has been demonstrated previously, these values closely correlate with those obtained from a pneumotachometer placed at the Y-piece/ETT interface [7].

The data were first collected as control data (no aerosol added) and then during the simulated administration of an aerosolized medication using saline in the Aerogen device. Inspiratory and expiratory Vt values were recorded for each breath. The PIP was monitored during the study. Data from a total of 250 ventilator breaths were collected using four modes of ventilation including two VCV modes (set Vt of 150 mL and 300 mL) and two PCV modes (set PIP of 15 cm H2O and 20 cm H2O). During each cycle, aerosolized saline (2 mL) was delivered via the in-line aerosol adaptor to simulate intraoperative medication delivery throughout all 250 breaths. Data from each individual breath were recorded on an Excel spread sheet.

Statistical analyses

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Inspiratory and expiratory Vt values during the control state were compared using a non-paired t-test to those obtained during the administration of the nebulized saline. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

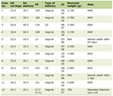

The inspiratory and expiratory Vt values with and without aerosols are listed in Table 1. Throughout the study during VCV, there was no change noted in the PIP which remained constant during the control trials and with the administration of aerosols. Volumes measured at the inspiratory limb by the internal machine sensor represent the inspiratory Vt on the table, and volumes measured at the expiratory limb represent the expiratory Vt. Regardless of the mode of ventilation (VCV and PCV) or the settings (PIP or Vt), the inspiratory and expiratory Vt as well as the PIP were essentially the same from breath to breath during the control phase and with the administration of the aerosol. Although the values reached statistical significance at some points, the change in the Vt with and without aerosol administration was less than 2.5% and therefore of no clinical significance.

Click to view | Table 1. Inspiratory and Expiratory Vt Values With and Without Aerosol Administration |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Intraoperatively or in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, various gases (such as helium or nitric oxide) or aerosolized medications (including bronchodilators, antibiotics, nitric oxide, surfactant, tranexamic acid, and mucolytic agents) may be administered for various therapeutic purposes [8-10]. Depending on the medication administered, various devices are available to aerosolize the medication and ensure distal delivery to the lungs even through an ETT including nebulizers, supplemental gas flow, or a metered dose inhaler (MDI) [11, 12]. While MDIs are delivered into the circuit without impacting ventilatory parameters, nebulizers which are dependent on external gas flows may alter Vt or PIP [13, 14].

Although pneumatically powered devices, including jet nebulizers, have been used during mechanical ventilation, novel devices, such as mesh nebulizers, have more recently been introduced and may offer specific advantages, as they do not require a secondary gas flow and may therefore not impact mechanical ventilation parameters. The Aerogen Pro device, that was used for our study, is an electronic nebulizer device that utilizes mesh technology to aerosolize medication during mechanical ventilation. The Aerogen device is usually placed along the inspiratory limb of the ventilator. The device contains a disc-shaped mesh plate with thousands of precision-formed microscopic holes that vibrate at an ultrasonic frequency [15]. The medication is placed in a small 6-mL cup that does not require opening of the circuit. The vibration of the disc aerosolizes the particles into a fine droplet mist as they pass through microscopic holes in the disc. This aerosolization process, as compared to high-flow or jet nebulizers, does not require a bias gas flow, limits added dead space, and therefore is not expected to alter ventilator parameters [13, 16-17].

The current study aimed to evaluate the impact of aerosol therapy with the Aerogen on ventilatory parameters (Vt and PIP) during intraoperative mechanical ventilation using a standard anesthesia machine. While previous studies have investigated how changes in ventilation parameters may influence the efficacy of aerosol delivery with different aerosol devices, there remains a relative gap in the literature regarding the inverse relationship on how aerosol administration may impact the set ventilator parameters including Vt [18-23]. In our study, even with the delivery of an aerosol, we noted no clinically significant changes in Vt or PIP regardless of the mode of ventilation (VC or PC). These findings did not change during two different set Vt (150 and 300 mL) and two varied pressure limits (15 and 20 cm H2O) when comparing the control state (no aerosol therapy) and active aerosolization with the Aerogen device, which was placed between the ETT and the Y-piece of the anesthesia circuit.

Other benefits have been previously reported with the vibrating mesh nebulizing devices. In general, these devices have been shown to be superior to jet nebulizers for the administration of albuterol in pediatric and neonatal patients. The vibrating mesh device achieves a higher lung deposition, reduces dead space, and limits extra flow compared to jet nebulizers. Using an in vitro pediatric lung model, the Aerogen mesh nebulizer has been shown to deliver up to three-fold more aerosolized albuterol than jet nebulizers during mechanical ventilation, noninvasive ventilation, and spontaneous breathing [12]. The efficacy of delivery and superiority over jet nebulizers may be impacted based on the site of placement of the mesh aerosolizing device with optimal delivery noted when the device is placed at the Y-piece and not at other positions along the circuit [22]. ElHansy et al analyzed the efficiency of aerosol delivery (salbutamol) during mechanical ventilation in 30 adult chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients using five different devices: the Aerogen Pro, Aerogen Solo, NIVO (vibrating mesh nebulizers), a jet nebulizer, and MDI AeroChamber-MV [24]. The devices were placed in the inspiratory limb of the ventilator downstream from the humidifier which was switched off during delivery. Efficacy of delivery was evaluated by measurement of urinary salbutamol levels. No difference was noted between the three vibrating mesh devices, all of which provided more effective aerosol delivery than the jet nebulizer. However, delivery was best with the MDI-AeroChamber-MV device.

In summary, the current study investigated the impact on intraoperative mechanical ventilation parameters during use of a standard anesthesia machine imposed by the addition of nebulization therapy with a vibrating mesh device. Although primarily used in the ICU setting, this device may be used in the operating room (OR); therefore, we chose to evaluate this device using a simulated OR setting with an anesthesia machine and its ventilator. With the device placed at the junction of the ETT and Y-piece of the ventilator, no changes were noted during various modes of PC or VC ventilation. The vibrating mesh technology is able to aerosolize medications without an added external gas flow thereby maintaining stable ventilatory parameters with a less than 3% difference from control values. The device used in the current study (Aerogen) was quick and easy to set up and operated silently during aerosolization of the medication. The Aerogen mesh nebulizer optimizes particle size by producing a consistent fine aerosol, allowing for tailored delivery. The study provides additional safety data supporting the use of these devices during mechanical ventilation.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Following the guidelines of the IRB of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, Ohio), informed consent was not required as there were no human subjects involved. This was only an in vitro evaluation.

Author Contributions

Data acquisition, preparation of initial, interim, and final drafts (AF); concept, design of the study protocol, writing, and review of all drafts (JDT); equipment procurement and review of final draft (AM)

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Kneyber MC. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation for the pediatric patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29(3):371-379.

doi pubmed - Spaeth J, Schumann S, Humphreys S. Understanding pediatric ventilation in the operative setting. Part I: Physical principles of monitoring in the modern anesthesia workstation. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022;32(2):237-246.

doi pubmed - Kneyber MCJ, de Luca D, Calderini E, Jarreau PH, Javouhey E, Lopez-Herce J, Hammer J, et al. Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1764-1780.

doi pubmed - Sawyer J, Moon K, Tobias M, Rice-Weimer J, Tobias JD. Accuracy of the set tidal volume during intraoperative anesthetic care: An in vitro evaluation. Int J Clin Pediatr. 2024;13:69-72.

- Bachiller PR, McDonough JM, Feldman JM. Do new anesthesia ventilators deliver small tidal volumes accurately during volume-controlled ventilation? Anesth Analg. 2008;106(5):1392-1400, table of contents.

doi pubmed - Kim P, Salazar A, Ross PA, Newth CJ, Khemani RG. Comparison of tidal volumes at the endotracheal tube and at the ventilator. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(9):e324-331.

doi pubmed - Aerogen Ltd. High efficiency aerosol drug delivery during ventilation: clinical white paper. Galway, Ireland: Aerogen Ltd; 2015. PM349.

- Chandel A, Goyal AK, Ghosh G, Rath G. Recent advances in aerosolised drug delivery. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108601.

doi pubmed - Singh S, Kanbar-Agha F, Sharafkhaneh A. Novel aerosol delivery devices. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(4):543-551.

doi pubmed - Chartrand L, Ploszay V, Tessier S. Optimal delivery of aerosolized medication to mechanically ventilated pediatric and neonatal patients: A scoping review. Can J Respir Ther. 2022;58:199-203.

doi pubmed - Georgopoulos D, Mouloudi E, Kondili E, Klimathianaki M. Bronchodilator delivery with metered-dose inhaler during mechanical ventilation. Crit Care. 2000;4(4):227-234.

doi pubmed - Ari A, Fink JB. Quantifying delivered dose with jet and mesh nebulizers during spontaneous breathing, noninvasive ventilation, and mechanical ventilation in a simulated pediatric lung model with exhaled humidity. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(8):1179.

doi pubmed - Lin HL, Fink JB, Ge H. Aerosol delivery via invasive ventilation: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(7):588.

doi pubmed - Li X, Tan W, Zhao H, Wang W, Dai B, Hou H. Effects of jet nebulization on ventilator performance with different invasive ventilation modes: A bench study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1004551.

doi pubmed - Dhand R. Nebulizers that use a vibrating mesh or plate with multiple apertures to generate aerosol. Respir Care. 2002;47(12):1406-1416; discussion 1416-1408.

pubmed - Dhand R. How should aerosols be delivered during invasive mechanical ventilation? Respir Care. 2017;62(10):1343-1367.

doi pubmed - Ari A. Aerosol therapy in pulmonary critical care. Respir Care. 2015;60(6):858-874; discussion 874-859.

doi pubmed - Berlinski A, Willis JR. Effect of tidal volume and nebulizer type and position on albuterol delivery in a pediatric model of mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2015;60(10):1424-1430.

doi pubmed - Ari A, Atalay OT, Harwood R, Sheard MM, Aljamhan EA, Fink JB. Influence of nebulizer type, position, and bias flow on aerosol drug delivery in simulated pediatric and adult lung models during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2010;55(7):845-851.

pubmed - Dugernier J, Reychler G, Wittebole X, Roeseler J, Depoortere V, Sottiaux T, Michotte JB, et al. Aerosol delivery with two ventilation modes during mechanical ventilation: a randomized study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):73.

doi pubmed - Ehrmann S, Roche-Campo F, Sferrazza Papa GF, Isabey D, Brochard L, Apiou-Sbirlea G, network Rr. Aerosol therapy during mechanical ventilation: an international survey. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(6):1048-1056.

doi pubmed - Berlinski A, Willis JR. Albuterol delivery by 4 different nebulizers placed in 4 different positions in a pediatric ventilator in vitro model. Respir Care. 2013;58(7):1124-1133.

doi pubmed - Lin HL, Chen CS, Fink JB, Lee GH, Huang CW, Chen JC, Chiang ZY. In vitro evaluation of a vibrating-mesh nebulizer repeatedly use over 28 days. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(10):971.

doi pubmed - ElHansy MHE, Boules ME, El Essawy AFM, Al-Kholy MB, Abdelrahman MM, Said ASA, Hussein RRS, et al. Inhaled salbutamol dose delivered by jet nebulizer, vibrating mesh nebulizer and metered dose inhaler with spacer during invasive mechanical ventilation. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:159-163.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Current Surgery is published by Elmer Press Inc.